Much of what Aquinas outlines is intuitive…they are things that as human beings, we can discover on our own. The problem most of us have, is that the true wisdom that leads us to peace and healing gets all jumbled up with things like cultural attitudes, the expectations from the people around us, and our own insecurities, fears, and doubts. It gets hard to figure out what to keep and what to set aside. It’s easy to reach for the things that numb us, and the pain seems better momentarily, but after the passing of time…hours, months, or years…we find that those things have really not helped us heal and the work of grief is still sitting in a disheveled pile, waiting for us to tend to it.

I can’t help but wonder, if I had found this list earlier, would it have helped me be more intentional about how I grieved? Maybe I could have let my tears flow more freely, knowing (from the wisdom of the wisest) that these tears weren’t a sign of weakness, but a sign of healing. Here’s the prescription from the doctor. May you find confirmation of your deepest needs, security, and comfort for your sorrow!

The Angelic Doctor’s Prescription to Remedy Sorrow:

Paraphrased for easy reading

1. Weeping:

Thomas Aquinas outlines two main reasons that tears and groans bring comfort to our sorrow. The first reason is that when we are hurting emotionally and we try to keep it all shut up inside of us, our souls become even more intent on the sorrow. However, if we allow the pain a path of escape, rather than turning in on ourselves, we can turn our attention outward and the inward sorrow is lessened. The second reason is that there is some level of comfort that comes from the honesty of showing on the outside what we are feeling on the inside. When our actions match our internal disposition, there is a level of pleasure that accompanies that congruency.

How many times did I feel like bursting into tears, and tried to keep them all trapped inside because it wasn’t a good time or place to cry, or simply because I was afraid to break the flood gate? I thought my tears had no “purpose” so I’d wrestle with them to keep them in. It is exhausting to try to hold that in. Eventually, I gave up trying. When I was in the store and something triggered my grief, I just let the tears do their thing. A little bashful about it, yes, but it brought so much more relief than trying to hold them in ever did! It turns out those tears do have purpose…their purpose is to bring healing to my soul.

2. Pleasure:

The doctor explains that pleasure is a kind of relaxation or peacefulness in our souls that occurs when what’s happening in the moment matches well with our wishes, hopes, and desires; while sorrow, on the other hand, is what we feel when there is a chasm between we want and what actually is. He gives us the analogy that pleasure is to sorrow, what, in bodies, rest is to weariness. Sorrow is a sort of weariness that comes from the gap that we feel, and pleasure is a rest in something that feels good or right or beautiful. Just as rest brings relief of weariness-- no matter what the cause of the weariness, pleasure brings some relief to sorrow--no matter the source of the sorrow.

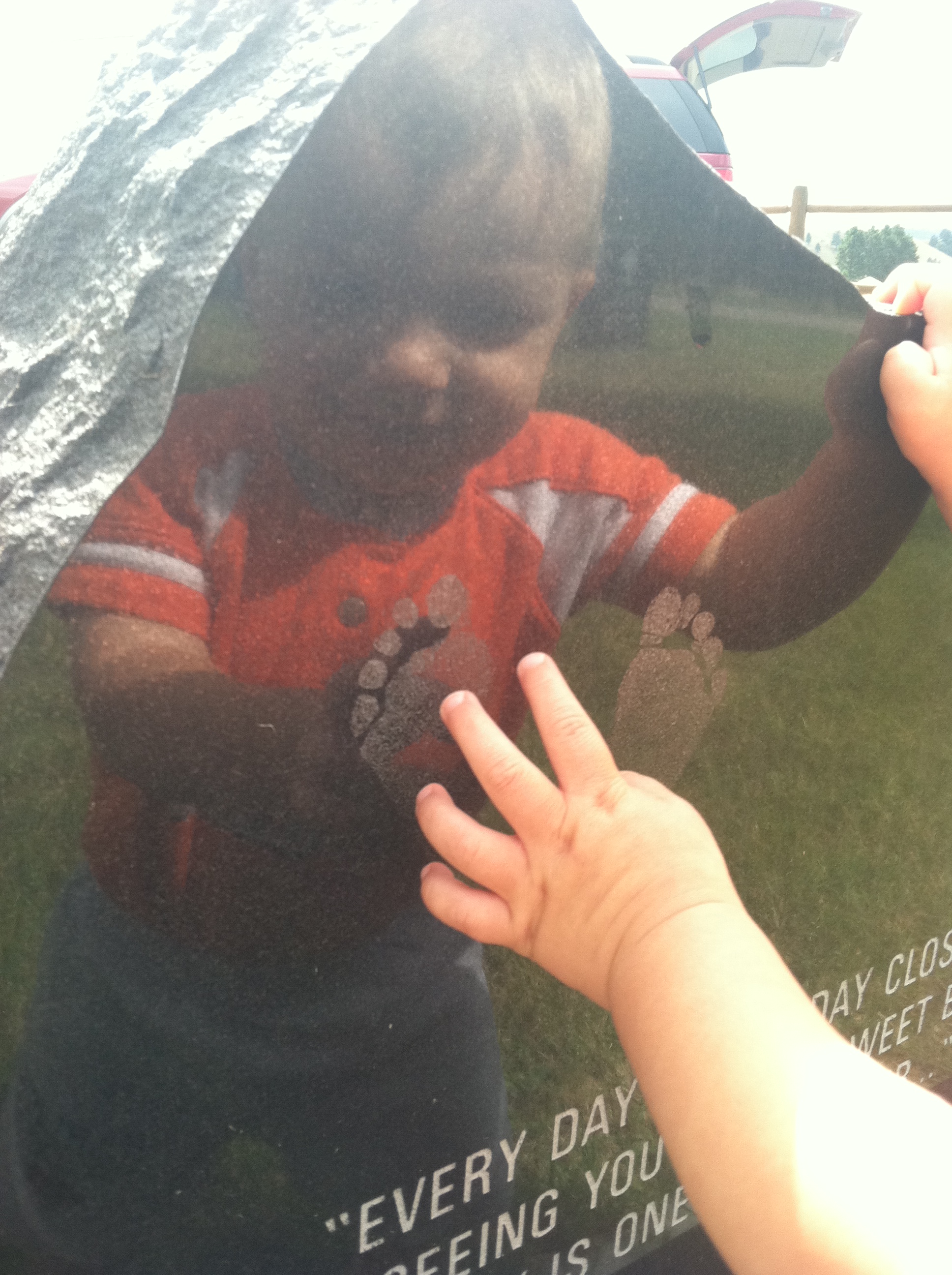

The sorrow that comes with a grief as big as the loss of a child can be all consuming. We are not capable of grieving and mourning 100% of the time…we need those little breaks that come from doing things that we enjoy, being with people who make us smile, in moments of lightness and laughter. It’s too easy to feel that doing something we enjoy, or daring to laugh or smile, is somehow a betrayal to our loved one and our grief. Aquinas shows us that finding times of enjoyment is not a betrayal, but an honoring of our grief. We know how deep our sorrow is and we can also know how essential moments of pleasure will be to bringing long-term healing and comfort.

3. Sharing Sorrow with Friends:

While it is natural to find that having the sympathy and understanding of friends and family is a meaningful source of comfort, Aquinas sees there are two reasons for the comfort. The first, he says, is because since sorrow has a depressing effect, it is like a weight that we strive to unburden ourselves of. When we see that others are saddened by our sorrow, it seems as though others are sharing in the burden of the weight and the load of sorrow becomes somewhat lighter. The second, and better reason, he states, is that because when friends sit with us in our sorrow, we see that we are loved by them…and feeling loved is the ultimate pleasure, and every pleasure eases sorrow, it follows that sorrow is lessened by a sympathizing friend.

How true this is! There were two main groups of people that were my sources of comfort. One, was other bereaved parents. They knew the burden, the ache, and the loss in a way that no one else can. They shared my sorrows, relieved my anxieties, offered me hope of healing, and lightened that heavy load. I was surprised at how connected I could feel with complete strangers or with people I barely knew because of this shared experience of loss of a child. The people who entered into my life because they had walked a similar road were an unexpected gift and a Godsend to me. It is largely what motivates my work of helping other bereaved families find those connections.

The second group of people were the people who loved me before my son died, and continued to reach into my life afterwards. The ones who shared my sorrow, not because they knew what it was like, but because they loved me. I concur with the Doctor. The second reason is the better reason. While I have made many dear friends from connecting with bereaved friends, there is something deeper, more soothing, and more comforting that comes from a sorrow that is shared out of love.

4. Contemplating the truth:

Aquinas asserts that the greatest of all pleasures consists in the contemplation of truth. Since we know from what was discussed already, that all pleasure softens our pain, then contemplation of truth is a valuable remedy to our sorrow. He also explains that the more comfort that you find from this remedy, the more perfectly you can be considered a lover of wisdom. He says, “And therefore in the midst of tribulations men rejoice in the contemplation of Divine things and of future happiness...”

Contemplating truth was a huge piece of my grief-work. The death of a child had no place in my world view, nor in my picture of an all-loving God. Yet, the hope that comes from the possibility of being reunited in heaven, made it impossible for me to walk away from the God that promised that. I needed to understand how suffering and a loving God can co-exist. I needed to know everything that is available about heaven and what it’s like…there were so many questions to be answered! What is it like there? Who is looking out for him and taking care of him? What might his experience be like? Does he feel the pain of our separation?

These things are hard. I had feelings of anger and betrayal toward God that I needed to work through. It didn’t happen all at once, but in tiny fragments. The work is not done. I’m still growing, still find new perspectives and understanding that is helpful. But this is the ultimate source of long-term healing and peace. A healing and comfort that is deep rooted and I think is one that will withstand in the storms that are undoubtedly yet to come.

5. Warm Baths & Naps:

Lastly, Thomas Aquinas prescribes bodily comforts, such as baths and naps. He says, sorrow, by its nature is offensive to the physical body; and consequently, whatever restores the body to its due state of wellness, is opposed to sorrow and lessens it. Moreover such remedies from the very fact that they bring nature back to its normal state, are causes of pleasure…and we know well by now, that pleasure assuages sorrow.

Contemplating truth and warm baths & naps. The juxtaposition is almost funny. Yet, I found those bodily comforts also had a valuable place in my acute grief. I was amazed at how much my body hurt, how physical grief could be. Every muscle was tense, my empty arms ached, I could feel the sharp edges of my broken heart, headaches and nausea became frequent companions. I needed to relieve the pain of my body. I found myself soaking in a hot bath regularly. I found reprieve in a good nap. I found that frilly coffees were a delightful comfort food. A good run, breaking a sweat, and moving my tight muscles, and the endorphin rush that comes with it found a regular place in my search for comfort.

Being medically minded, the analogy that comes to mind is this: Like many things in medicine, when a patient presents in severe pain, we dull the pain with a pain medication which is valuable to the comfort of the patient, but then we have to work to heal the body on a deeper level. Pain medicine is not enough for the long haul, but they sure do help get through the most excruciating pain. Baths and naps are the pain medicine, the immediate comfort; contemplating truth is the deeper healing plan.

Take these remedies and hold them near, explore them, and see if this wise old Doctor really knows his stuff. I think you’ll find that he does!